About article one:

Creating your own symbols: beginning algebraic thinking with Indigenous students.

Matthews, Christopher and Cooper, Thomas J. and Baturo, Annette R. (2007)

Retrieved from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/14627/1/14627.pdf

It is important when reviewing culture to see where the main challenges lie. Indigenous students continue to be the most mathematically disadvantaged group in Australia. The believed reason surrounding this claim is that current mathematic pedagogies do not include the models of the world Indigenous people have created to inform their knowledge. As a result, this challenges their identity.

Mathews et al., (2007) have depicted a way to contextualise mathematics within the Indigenous culture and perspectives. This aims to bring forth a strong sense of pride for students that hold Indigenous identity and culture. This focus on effective strategies to teach mathematics to Indigenous students is crucial as it can determine their employment and life chances.

Firstly, it is crucial to understand how Indigenous students learn best:

- Contextualised concrete “hands-on” tasks (Gool & Patton, 1998).

- Provide “greater sensitivity and success in dealing with visual and spatial information compared to verbal” (Barnes, 2000).

- “Learn by observation and non-verbal communication” (South Australia DETE, 1999).

It is recognised that non-Indigenous teachers struggle with contextualisation, therefore it is suggested that partnerships are built between teachers and Indigenous teacher assistants (employed from communities). This is ideal as the subject mathematics is classified as an ‘at risk’ area for Indigenous students. By increasing mathematical awareness Indigenous students will be gaining higher employment opportunities.

Looking into a specific area of mathematics, it is believed that developing algebra capabilities will be the most useful for the following reasons addressed:

- Algebra is the fundamentals of many high-status progressions

- Algebra deals with generalising pattern and structure, relatable to the Indigenous culture, as a lot of their experiences and past downed knowledge is explained through patterns and structure (e.g. kinship systems).

- Algebra drives all other mathematical concepts, and having this understanding will make mathematics simple, because you can see and understand the patterns and structure within different concepts.

Therefore, to explore culture within mathematics, and how to maximise understanding to create stronger users of mathematics (within the Indigenous culture) the article focuses on representing mathematical equations as stories. This contextualises it for Indigenous students as symbols are drawn from their socio-cultural background. This means mathematics can be described through story telling and the analyse of it will be in terms of Ernest’s (2005) semiotic processes.

To apply mathematics through a story telling approach, 5 steps are explored, these steps summarised:

- Students learn the meaning of symbols and how they are ordered to create a story. This will be introduced through looking at Indigenous situations (symbols within ancestors’ paintings). Then symbols that interpret simple actions will be explored.

- Students will physically act out a story to generate discussion and to identify the parts of the story and the action within. This will create a visual, action-based interpretation.

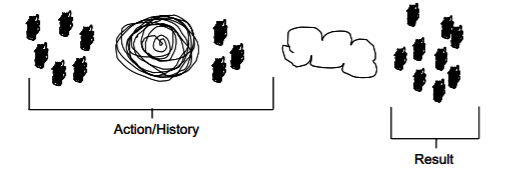

- Students will start to create their own symbols to represent a story. This is done with some teacher direction. The teacher will explain that students must include two action symbols that result in something (this is called an addition story). See Figure one.

- Students will discuss their symbols within a group, this is where they will discuss what each symbol means/represents, help students use language such as “resulting in””coming together” “altogether”. The progression of this learning sequence will be for the class to decide on a symbol system to use (this can be added overtime), then the teacher will present another addition story. This step is crucial as students are learning to write and adapt different symbol systems, and gradually this should lead to an agreed upon, standard classroom symbol system.

- Lastly students will begin to modify the story, this will be where algebraic ideas are introduced. To begin this step, explicit teaching will be done. The teacher will take an object from the action part of an addition story. The teacher will question whether the story still makes sense (answer should be “no”). The teacher will ask students to find different ways that can help the story to make sense again. They should explore different possibilities as a class (putting an object back, adding another action, taking an action from the result side). This will play with algebraic terms such as the notion of compensation and equivalence of expression, balance rule (equivalence of equations).

Figure one.

The above steps use the semiotic method for the teaching and learning of mathematics as they include the using and understanding of signs. The five steps are an illustration of how mathematics through story telling can be used to introduce students to algebraic ideas, while the semiotic side shows the implications of the approach for bridging the gap between arithmetic and algebra.

Blog one (how my thinking about mathematics is impacted by article one).

I found this article extremely interesting, I enjoyed how they thoroughly explained how implementing this pedagogical approach to mathematics can enhance cultural awareness. Although teachers can attempt different approaches to teaching, being able to explain why they are culturally inclusive and how to create cultural activities from knowing why, is where I believe the comprehension gap in mathematics lies for indigenous students.

I found this article provided enough information that it creates an opportunity for all classroom teachers to attempt the introduction and emphasis of symbolism, according to the indigenous use of it. Although I am familiar with Aboriginal paintings and that they include symbols that tell stories, I never would’ve understood how to relate it to mathematics and seeing how this can be a culturally inclusive way to teach algebra within mathematics.

Whilst I was reading this article, what also crossed my mind was the question: can this be an activity that non-indigenous students enjoy? I am non-Indigenous and initially I didn’t think so, as I went in thinking I don’t know much about the Indigenous symbols and their underlying meaning. However, the more I read about this activity and the different way it presents algebra intrigued me. I therefore came to conclusion that I believe this activity would be enjoyed amongst all students, especially those who are non-Indigenous but are visual learners or creative thinkers (which a majority of primary students are as they are still young and enjoy creative, hands on learning).

What I also gathered and liked was how this cultural related, teaching strategy of algebra gave students the chance to create their own symbols. This can appeal to the creative kids in the class and the weaker readers. It can also derive on a lot of pre – existing knowledge of students, especially Indigenous, as they may choose symbols that are actually used within their culture or have been shown to them by their Elders. It could also trigger Indigenous students to go home and ask about symbols to their Elders and family.

Finally, I feel having an Indigenous leadership presence and/or assistant within a classroom for regular mathematic lessons is an idea that could very much benefit a teacher to be able to build those cultural links and understandings. This can mean that Indigenous students are eventually subjected to their culture in lessons, and that non-Indigenous students are building their cultural awareness and inclusivity.

About article two:

It’s time we draft Aussie Rules to tackle Indigenous mathematics.

Christine Judith Nicholls, Senior Lecturer at Flinders University (2013).

Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/its-time-we-draft-aussie-rules-to-tackle-indigenous-mathematics-15032

‘Mathematics and Aussie Rules have quite a lot in common, which should be used when considering curricula for Indigenous – and non-Indigenous – students.’ (Nicholls, 2013)

Another perspective on a strategy to integrate mathematics into the Indigenous culture is through sporting activities, which are known to be a major area of interest within the Indigenous Australian culture. In Australia the Indigenous frequently excel at the sport Aussie Rules. This investigates their learnt cognitive factors and the hard work that goes into their success.

The researcher of this article, in 1980 through to the 1990s, lived and worked as a school principle in the Warlpiri settlement of Lajamanu in the Tanami Desert (between Alice Springs and Darwin). Throughout her time, she watched numerous young Warlpiri men

and women play home based AFL games. She described these games as “dashing, thrilling football”(Nicholls, 2013).

Nicholls (2013) was astonished by the consistent skills these young Indigenous footballers continued to bring to each game over the years and genereration to generation. They can grab hold of an airborne football flying from any direction, whilst running at full pelt. Their ability to then find a passage through a narrow corridor, followed by the finely tuned accuracy of their near-vertical jumps is inspiring (Nicholls, 2013). This brought forward the question “in what ways might Indigenous youth’s early childhood learning experiences and socialisation patterns lead to greater-than-average success in the game of AFL?”

Nicholls (2013) attempts to answer this question by firstly referring to the link between the 360-degree nature of the game and the Indigenous cultural use of cardinal direction language to consistently orient oneself in an environment with minimal features (football field). The specific spatial abilities being used within this game can relate in a cross curricular way. Learning areas such as Number, Algebra and Geometry strands within the Australian Curriculum can all relate to this game, if depicted carefully.

Nicholls and Cooke (2013) explore the shape of the field, angles at which a ball is kicked to score a goal and the positioning/distancing of players regarding other objects on the field. It is said that cardinal directions are the way Warlpiri communicate directions; left and right have a different meaning for Indigenous students and non-Indigenous teachers. This suggests that compass directions (North, South, East, West) should be taught before left and right as it is inclusive of this culture.

In all subject areas within the Australian Curriculum the goal is to know the content and how to teach it. When looking specifically at the Indigenous culture and developing their knowledge in areas such as mathematics, it goes beyond inclusion of “Indigenous perspectives” but foregrounds “Indigenous knowledge”.

Blog two (how my thinking about mathematics is impacted by article two).

What this article did well was provide an in-depth example of a context specific way to go about introducing mathematical concepts. I have grown up in Darwin, Northern Territory which has a strong Indigenous presence. This means when the author of this article was explaining that the Indigenous culture very much includes being outdoors and taking part in sporting activities, I was able to easily relate it to my surroundings and agree. What I have observed personally (like the author of this article) is that younger Indigenous students love and get excited about the outdoors and getting sport time, as this is something they easily relate to and are use too. In primary schools you see teachers use ‘sport time’ as an incentive to get students to class and to get them to attempt their work. What I haven’t seen, and really engaged with was how the author of article used sport to learn instead of as an incentive. This is clever as students will drive of those connections and be engaged as it is something they can visualise, comprehend and gradually build on that knowledge further.

What I initially questioned was what about the non-sport lovers? But that got me thinking, you would still be able to show them so they can visualise, this could be done by taking them out to a sporting area (field, court, pool. etc) and showing them. Also, as teachers we know our students, what drives them, therefore we would know other outdoor/indoor activities that they enjoy. From knowing this we can explore other mathematical skills students may unwarily use and inform them.

Although this article is different to the first article (in terms of what is being explored/discussed), it is similar in the way that it is depicting the interests and driving on familiarity of the Indigenous culture. Using this to a teacher’s advantage is what can potentially lead to greater success for Indigenous students in the learning area mathematics.

About article three:

Indigenous mathematics: Creating an equitable learning environment.

Grace Sarra, Senior Lecturer, Queensland University of Technology (2011).

Retrieved from: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1118&context=research_conference

Mathematics according to Sarra (2011), has consistently been a learning area in which Indigenous students struggle to achieve satisfactory results. This has been identified as mathematics is believed to be a Eurocentric subject. This consequently creates a struggle when attempting to contextualise pedagogy with Indigenous culture and perspectives.

Sarra (2011)explores the YuMi deadly centre, which focuses on pedagogies for Indigenous learning. YuMi Deadly combines a Torres Strait Islander word (YuMi) meaning ‘you and me; and an Aboriginal word (deadly) meaning ‘smart’. The centre is run by mathematic educators and educators that specialise in Indigenous philosophy and pedagogy and school change and community involvement strategies.

The philosophy of YuMi Deadly is from the realisation that mathematics is an abstraction of everyday life. It presents mathematics by viewing it as a living, growing creative act in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students can achieve by active participation and the valuing of Indigenous communities’ ways of knowing and doing.

The article encourages that YuMi should be a whole-school-approach. This approach aims to achieve five key objectives, these summarised:

- Acknowledging, embracing and developing a positive sense of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity.

- Creating positions for Indigenous leadership/role models in schools and communities.

- Building and maintaining strong community-school partnerships.

- Maintaining high leadership and classroom expectations

- Ensuring productive teaching and learning pedagogy is meaningful to the social and cultural contexts of the Indigenous learner.

These objectives implied are expected to enhance the performance of Indigenous students. Firstly, it is crucial to understand that Indigenous students are not under-performing (in mathematics) because of their innate intelligence, nor is their social and cultural background at fault. Sarra (2011), believes what is needed is for educators to examine the structures and cultures of the education system that are the link between school practices and Indigenous student outcomes.

This article also explores what mathematics’ involves. In comparison to the first article explored (Creating your own symbols: beginning algebraic thinking with Indigenous students, 2007) this article also believes there is success found within the usage of symbolic language. According to Dr Chris Matthews (2008), students should create their own mathematical representations, and explore solutions to problems by relating their mathematical representations to situations within their world view.

Gradually this should introduce correct mathematical symbols. We are not to just present these to the students we are to derive the meaning behind them, showing them that mathematical concepts are related to their own perceived reality. This really focuses on the initial ability to select a certain part of reality, what we deem to be important, and the symbols we create to represent meaning.

Another point emphasised is that it is also important for teacher to be able to relate mathematics to their culture. This will show the teacher that mathematics can be related in a cultural context. Perhaps this could open minds to different ways in which we can understand and teach mathematics, so it’s not so ‘just sitting and working through a mathematic worksheet’.

Blog three (how my thinking about mathematics is impacted by article three).

This article really introduced me to the introduction of a whole school approach. What I like about a whole school approach is that it makes sure all teachers are teaching the same material and have the same intentions. What I don’t personally like about a whole school approach is that it doesn’t really include the individual needs of students. A whole school approach can go off the general requirements, however each year, each student is different, and I think instead of being limited to a whole school approach it is more important to cater for the individual students within your class, each year.

I believe having access to more cultural inclusive resources that explains how you can create a lesson that builds off culture is a better way to ensure a more inclusive approach. I also think professional development opportunities that show you examples of taking something Indigenous students can be interested in and how to initially go about creating a lesson out of that. What should we be asking them to trigger prior knowledge?

This article also shared details on how to introduce symbols into mathematics. However, it wasn’t as explicitly explained like the first article which made better links to the Indigenous culture. Nevertheless, its good to see a link between articles and their content and ideas, this reinforces that it is a well proven, effective, teaching pedagogy.

Finally, what I found interesting in this article and never thought to do was firstly look into my own culture and depict mathematics from things that create it. Then ask myself how I taught myself that and how I could explain it, so others understand? How do I visualise it? This is harder than you think, but I feel with experience will come the gradual ability to see mathematics in everyday life and different ways in which we can teach it.

My culturally responsive pedagogical approach:

Going forward after researching the culture within mathematics, it has allowed me to consider how I would start creating a culturally responsive pedagogical approach, that is inclusive of Aboriginal students in mainstream classrooms. As education in todays society has moved towards creating an inclusive environment, there is a lot of information about how to cater for the likes of ESL students and students with learning disabilities such as ASD. However, although there is information out there, it is still extremely limited and more professional development for teachers is needed regarding culture in main learning areas such as mathematics.

Cultural inclusion is so much more than just having resources available to students in the classroom. It is about the teacher having the ability to create lessons based on students’ culture. This is done by triggering their understanding and reviewing how they have grown to understand what they already know. In aim of extending that knowledge by building on from this in a similar way that they continue to understand. This looks beyond things such as worksheets, note taking, and the occasional reference to different cultures.

I believe if I was to present a pedagogical approach to including culture it would need to firstly look into finding out what students like to do, what they are interested in, how have they learnt in the past, learning areas or concepts they already excel in. I would use this knowledge to then get them to explain to me their understanding and techniques in areas of interest such as sports. From this I would begin to create a lesson that shows them how they are using mathematics to develop this understanding and skills they already have. This would be through practical, hands on, learning such as taking a basketball out and discussing angles before shooting, or creating maps through symbols they know from their cultures, getting them to pretend to be a coach and scale down a football field and game play.

Indigenous students are most of the time visual, hands on learners and creators. This is how their culture has taught them to understand, and it’s our job to create and continue these cultural opportunities so they continue to connect with their culture and understand, but at the same time provide them opportunities to create new knowledge and learn different ways to understand.